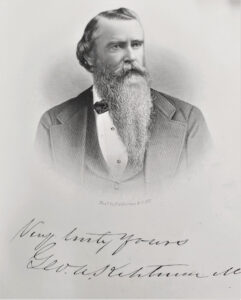

Dr. George Augustus Ketchum (1825-1906) who organized the Bienville Water Works in 1886. Courtesy Historic Mobile Preservation Society

George Ketchum practiced medicine in Mobile for nearly 60 years and was a founder and dean of faculty at Mobile’s Medical College of Alabama until his death in 1906. The fountain, dedicated in 1890, was a thank you for his establishment of the Bienville Water Works in 1886.

The Bienville Water Works was not the city’s first. On December 20, 1820, the Mobile Aqueduct Company was chartered to bring fresh water to the city from Three Mile Creek. By 1824, nothing had been accomplished and the plan was scrapped.

Mobilians had to collect water from public pumps around the city or dig their own wells. The proximity of many of these wells to the family privy certainly accounted for an increase in diseases. In 1836, Mobile’s Henry Hitchcock met with a German-born engineer to discuss the possibilities of building a modern water works for Mobile.

The Stein Water Works

Albert Stein had a proven 20-year record at that point. Trained as a hydraulic engineer, he had been involved with building the water works in Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Richmond, Nashville and New Orleans. In December of 1840, 20 years after the first try at a water system, the city was finally going to have one.

A 20-year contract was prepared and Stein agreed to have the system running within two years. He used water from Three Mile Creek and sent it through 30-foot pine logs with a 4-inch hole bored through the centers. Just what sort of water pressure was possible with this system is unclear, and there was no mention of fire hydrants.

In May of 1860, Albert Stein was fined $2,000 by the State of Alabama for “supplying the people of Mobile with poisonous water.” A number of lead pipes had been used in his water system and his conviction was based on “the poisonous quality of water induced by its passage through lead pipes.”

A year later, that conviction was overturned by the U. S. Supreme Court, which ruled Stein had no prior knowledge of the poisonous consequences of using lead piping.

Mr. Stein would provide water for Mobile until his death in 1874, long after his contract with the city had expired. His son, Louis, continued running the water works.

With the economic depression of the reconstruction years, Mobile’s economy was at a standstill. By 1879, things had reached a low point financially and Mobile’s city charter was repealed. Mobile was now officially The Port of Mobile.

An Expanded Need

Improvements to the port over the next few years led to increased exports and the state legislature reestablished the charter for the City of Mobile in 1886. On April 9 of that year, Dr. George Ketchum organized the Bienville Water Works, extolling the idea that a good supply of clean water equated with better health.

The city was growing and expanding and Ketchum wanted it to have an adequate water supply. His other selling point was the installation of fire hydrants, which would lead to lower insurance rates for residents and business owners. In September of 1887, a crowd cheered when a stream of water from a newly installed hydrant was propelled 15 feet above the flagpole atop the Battle House Hotel.

Rather than taking water from Three Mile Creek, the Bienville Water Works chose Clear Creek off Moffett Road and began laying water mains leading into Mobile. The 20-year contract also included providing water for domestic and municipal purposes to the city and “the Village of Whistler.”

As the pipes were being laid “like spider webs” around Mobile, Louis Stein was meeting with his attorneys. On April 25, 1887, Stein filed suit claiming that the establishment of another water works was a violation of his father’s 1840 contract with the city.

After losing the case locally, Stein took it to the Alabama Supreme Court and ultimately to the U. S. Supreme Court. The justices agreed with the lower court. Stein had the right to pump water from Three Mile Creek and Bienville Water Works had not touched that source. Stein sold out in 1898, and his plant was closed in 1901.

It has gone unrecorded what Mr. Stein thought of the fountain honoring the organizer of the Bienville Water Works but it is a good bet he was not present at its dedication. Dr. Ketchum’s office on St. Francis Street offered him a clear view of the fountain, which has now been restored and reinstalled.